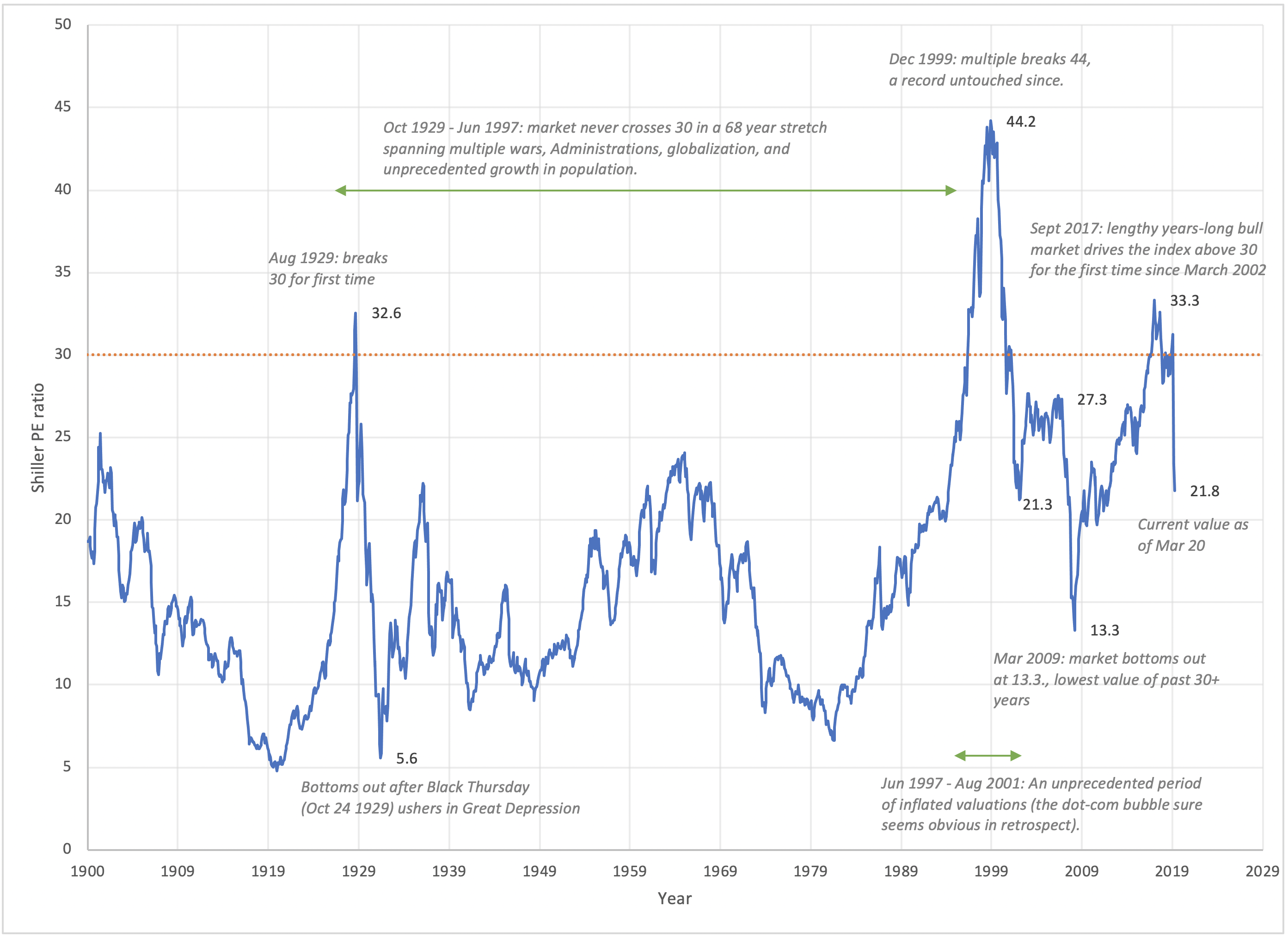

The above chart can be split into a few different periods (described below), but you notice a few things off the bat:

- Median values are about 16, i.e., 16 times earnings has historically proven to be the going-rate for a company in the S&P500. So if you had to randomly pick an S&P500 company out of a hat at a random point in history, and I told you the earnings of that company and asked you to guess the price, you should say 16 times earnings.

- Anytime the index breaks 30, it always falls back below 30. The longest stretch above 30 was around the dot-com boom, and it lasted 51 months. The index has only broken 30 on three occasions: the leadup to the Great Depression, the dot-com boom, and the leadup to whatever it is we call what's happening right now.

- Right now we’re at 21.8 , which is well off the highs of the last few years, but is still considerably above average. In other words, there is a lot more room to fall in 2020. The 1929 crash led to a fall from 32.6 to 5.6 (-83%). The dot-com bust led to a fall from 44.2 to 21.3 (-52%). The 2008 financial crisis led to a fall from 27.3 to 13.3 (-52%). How far will we fall from the 2017 high of 33.3? Given generally favorable macros for stocks (including low interest rates), I think an 80+% fall like that of 1929 is highly unlikely. But in both 2001 and 2008 crashes, the index fell by more than half. If that happens now, we’d be looking at something closer to 16 over the next couple years, which coincidentally is close to the historical average of the index.

For investors who take a long-term view towards the markets, I do think this represents an opportune moment to buy some good companies at reasonable prices. The key, as always, is to make measured decisions and to NEVER put yourself in a position where you have to sell stocks when you don't want to. There is perhaps no greater destroyer of wealth in the stock markets than people selling either out of fear or out of necessity at the bottom of markets.

Mar 14th 2020

COVID-19: Can we learn anything?

Wednesday, March 11th really marked the turning point for coronavirus in the United States. On this day, (1) the NBA suspended its season, paving the way for mass cancellation of pretty much every major sporting event, (2) the first celebrities announced positive tests (Tom Hanks and his wife and Rudy Gobert of the NBA), with many more following over the subsequent days, including heads of state and (3) President Trump delivered an address that, at a minimum, seemed to finally acknowledge the gravity of the situation. Undoubtedly, things are going to get much worse in the US before they get better, and there are likely to be thousands of needless deaths, in a best case scenario. There are also as of yet unsubstantiated anecdotal claims that the virus may be capable of causing permanent lung damage, so even those who are infected and survive (which is the vast majority of individuals), they may be dealing with some medium- and long-term negative health outcomes from the virus.

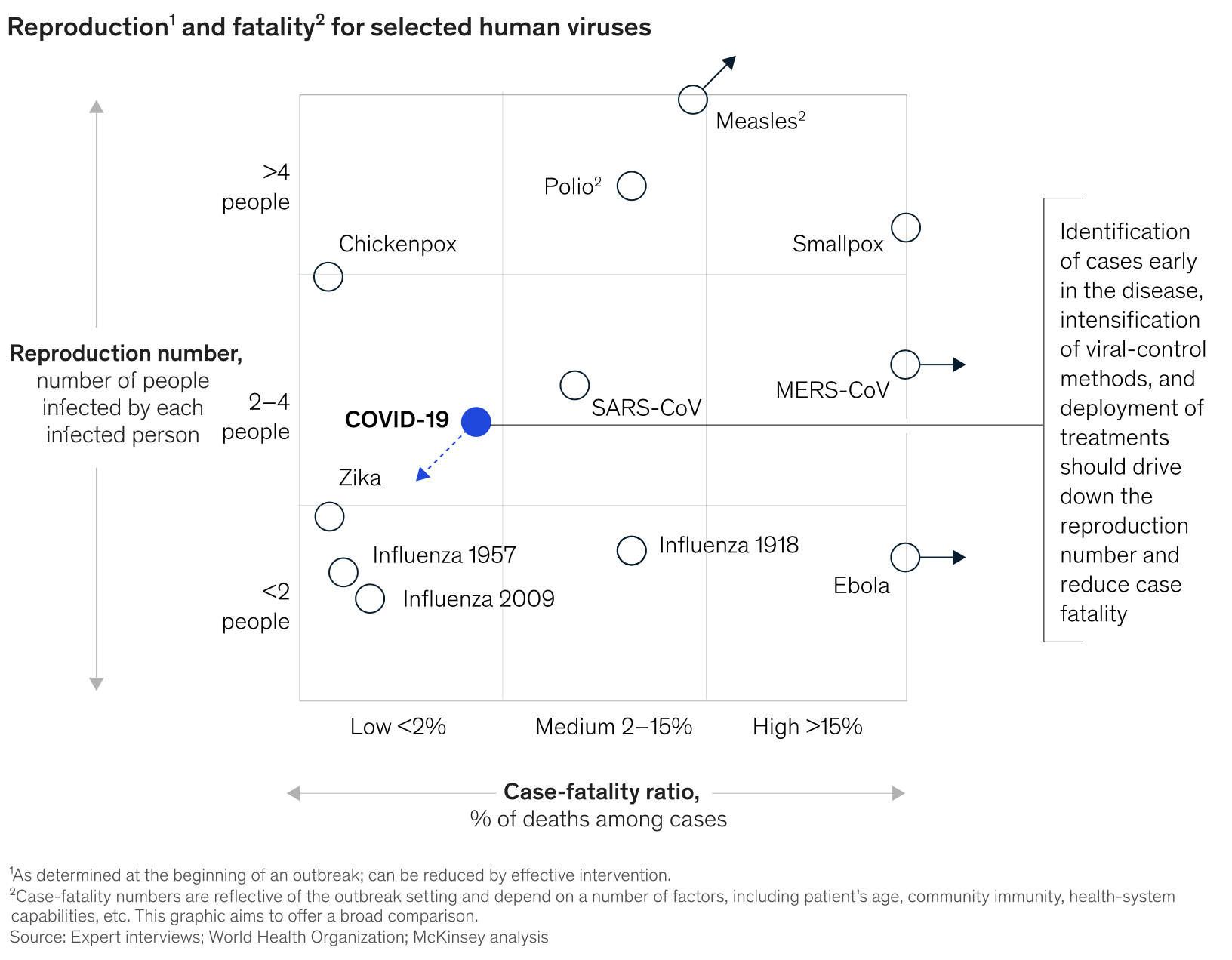

The virulence of the virus appears to significantly exceed that of typical influenza strains: for every

person who contracts coronavirus, they’re likely to infect 2-3 others (so called reproduction number, or

R0 of 2-3). Most influenza strains are below 2. Some of history’s most famous viruses, like chickenpox,

polio, smallpox, and measles, exceed 4, so they are dramatically more contagious than coronavirus. In terms

of lethality, coronavirus is actually on the low end when compared to history’s most famous viruses. Its death

rate appears to be well under 2% (and likely closer to 0.5%), which is substantially lower than SARS, Spanish Flu of

1918, polio, measles, and dramatically lower than smallpox, MERS, and Ebola, which are 3 of the most deadly viruses

ever. However, it is considerably more deadly than the standard pathogens that most humans experience on a seasonal

basis. My former employer (McKinsey), put out a short paper on the coronavirus, which I would encourage people to

read here,

and I’m including what I consider the most interesting chart from that paper below.

As American society begins to really grapple with the virus and what it means for our lives in both the near- and long-term, I’ve been trying to find some potential positives that could come out of this situation. What can we learn from an event like this that makes us stronger and more resilient moving forward? My thoughts on this are evolving every day, but a few things immediately jump out at me:

- A faster, more efficient FDA: I have many problems with the FDA, their processes, and how slow things often move. Roche, the Swiss healthcare giant, was given expedited approval for a coronavirus test in around 24 hours, which, as you can imagine, is dramatically faster than standard processes. The FDA will hopefully learn from this (with the proper push from the White House) to figure out ways to accelerate their standard procedures. This could mean other life-saving drugs are made available to the US public sooner, which is, without question, a step in the right direction.

- Rapid vaccine development: many of the best and brightest minds in the world are now focused on a coronavirus vaccine. This is undoubtedly the largest concentration of brainpower and financial resources directed at vaccine development in human history. The learnings from this effort will accelerate vaccine development, helping us to be better prepared for future viruses that lie in wait.

- New growth in US manufacturing: the virus is a boon for non-globalists who decry outsourcing of US manufacturing. Undoubtedly, the government will almost certainly be stepping in to encourage (or, in the case of some critical items, to force) manufacturers to bring capacity into the United States. I suspect bipartisan legislation to this effect, regardless of the outcome of the 2020 election.

- More robust US supply chains: shocks like this have a way of breaking weak systems. Many companies are learning a hard lesson in relying on supply from one country or region. Expect large companies to find additional ways to diversify their supply chains, creating a much more robust network moving forward, through a combination of US manufacturing insourcing and supplier diversification.

- Uniting people against a common enemy. There are very few situations where the world, at once, feels like it’s all fighting the same thing at the same time, hoping for the same result. I remain hopeful that the virus reveals some humanity in all of us that’s often buried under the trivialities of daily life.

Feb 9th 2020

Uncertainty and seed-stage companies

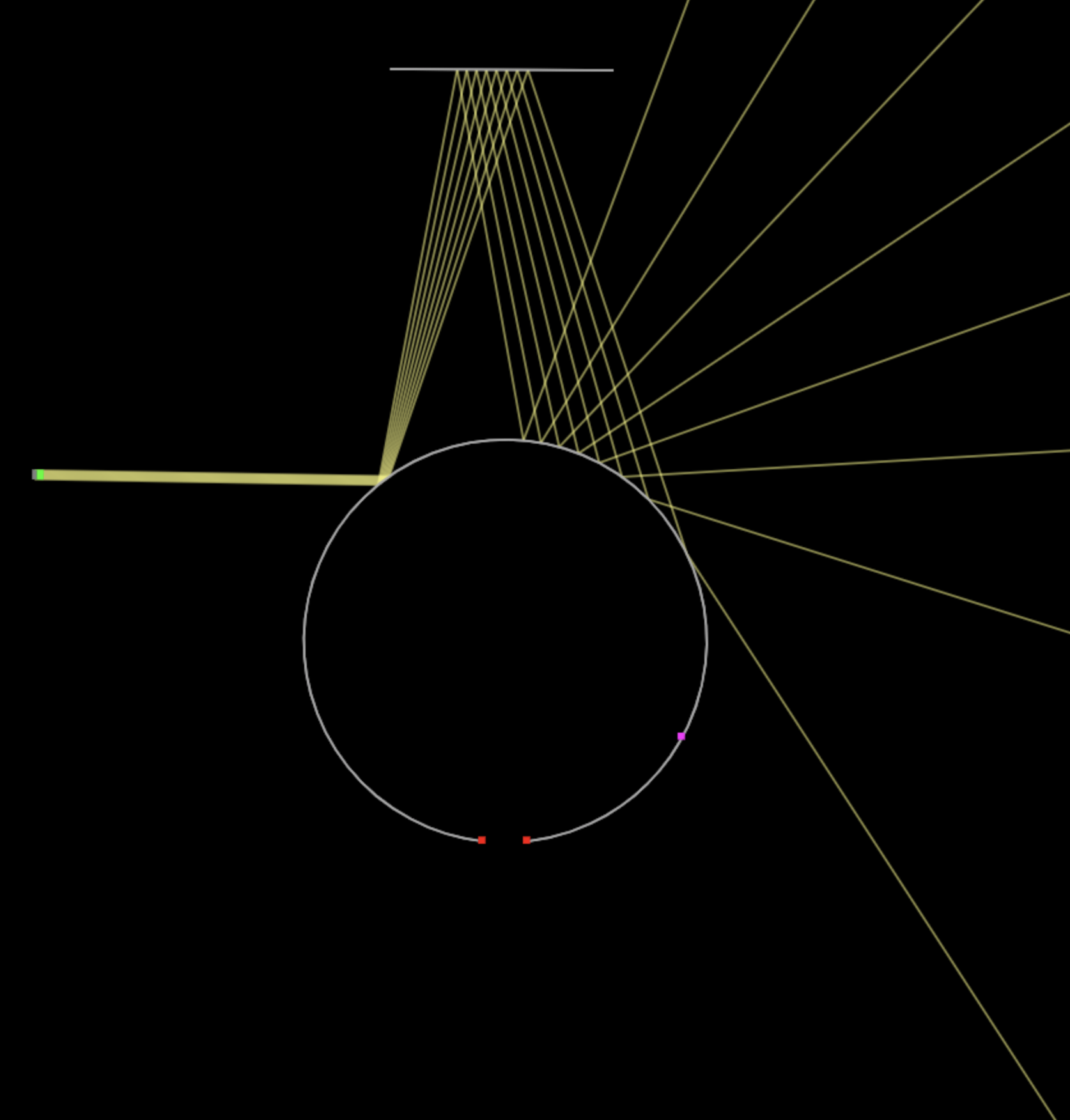

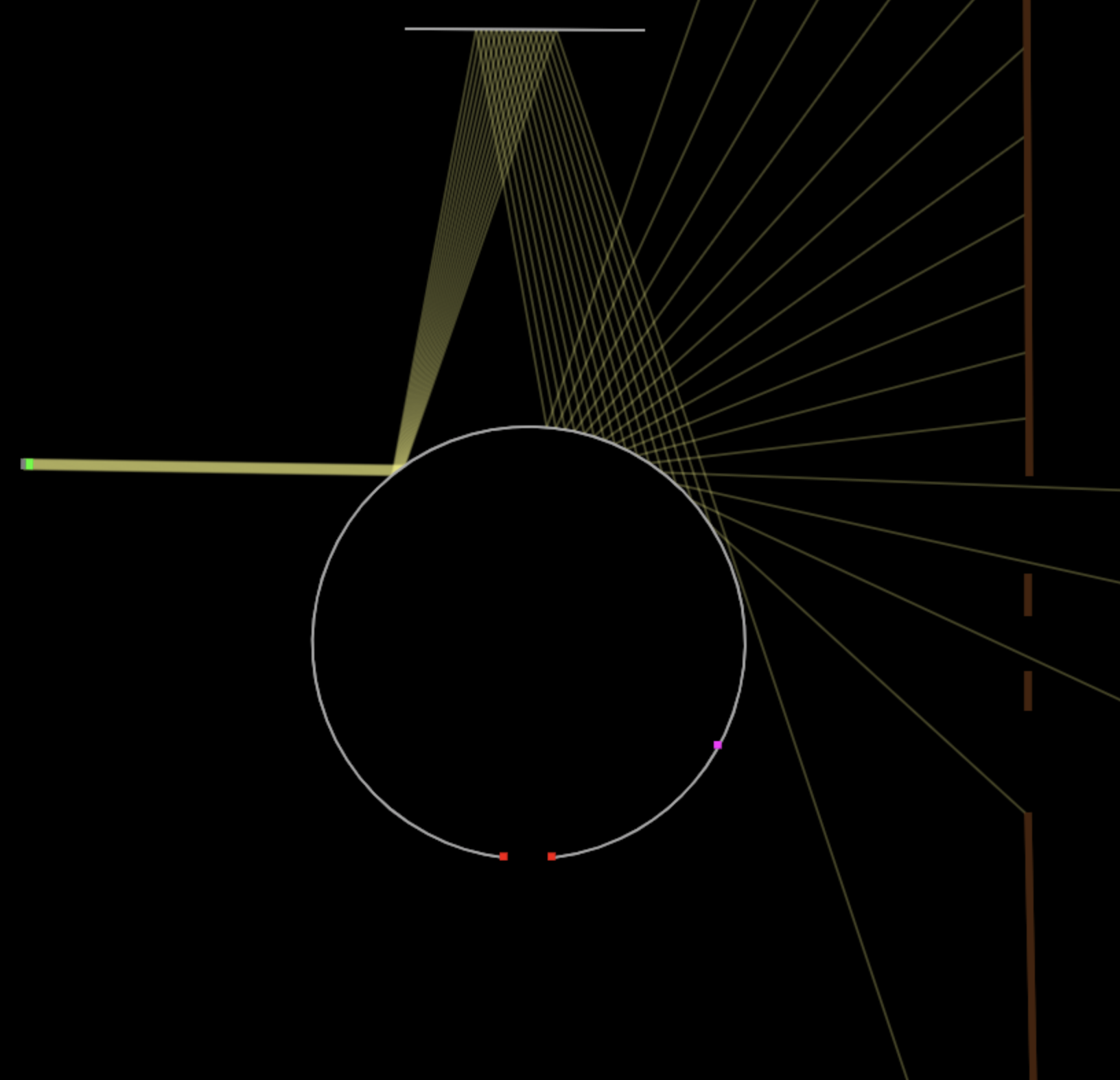

There’s an image in Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s book “The Black Swan” that really resonated with me. It has to do with the concept of uncertainty, and how small deviations in starting conditions can produce massively different outcomes. The image looks something like the below:

Imagine you have a bunch of light rays, each represented by a yellow line, heading towards a circular mirror. The light rays are all heading in the exact same direction, but their starting positions differ slightly. When the rays are reflected off the circle, the small differences between the rays become bigger. Subsequent reflections off a straight mirror (at the top of the image) and then back off the other side of the circle amplify these differences even further. By the end, the rays end up heading in completely different directions. Some are going up, some are going down, and some are headed in roughly the same direction as when they began. All this despite the fact that, when they started, they were heading in exactly the same direction with only small differences in their starting point. This phenomenon has many names (“butterfly effect” being a popular one), and it has a number of consequences on our lives. It’s connected to ideas like false precision, chaos theory, and fat-tail distributions. But the fundamental idea is this: small differences can lead to massively different outcomes. One area where I like to think about this effect is regarding the role seed-stage funds play.

Think of a startup company as one of the light rays shown above – each startup is equivalent to 1 of the 8 yellow lines shown. Inevitably, a startup will have obstacles in its path to success. It will have to navigate around these obstacles, change directions (“pivot”), and hopefully get to a point where it’s moving forward in a direction it wants to be going. Obviously, a startup is navigating a far more complex environment than the one simulated above, but the key principle remains relevant: small differences in conditions can lead to massive differences in outcomes.

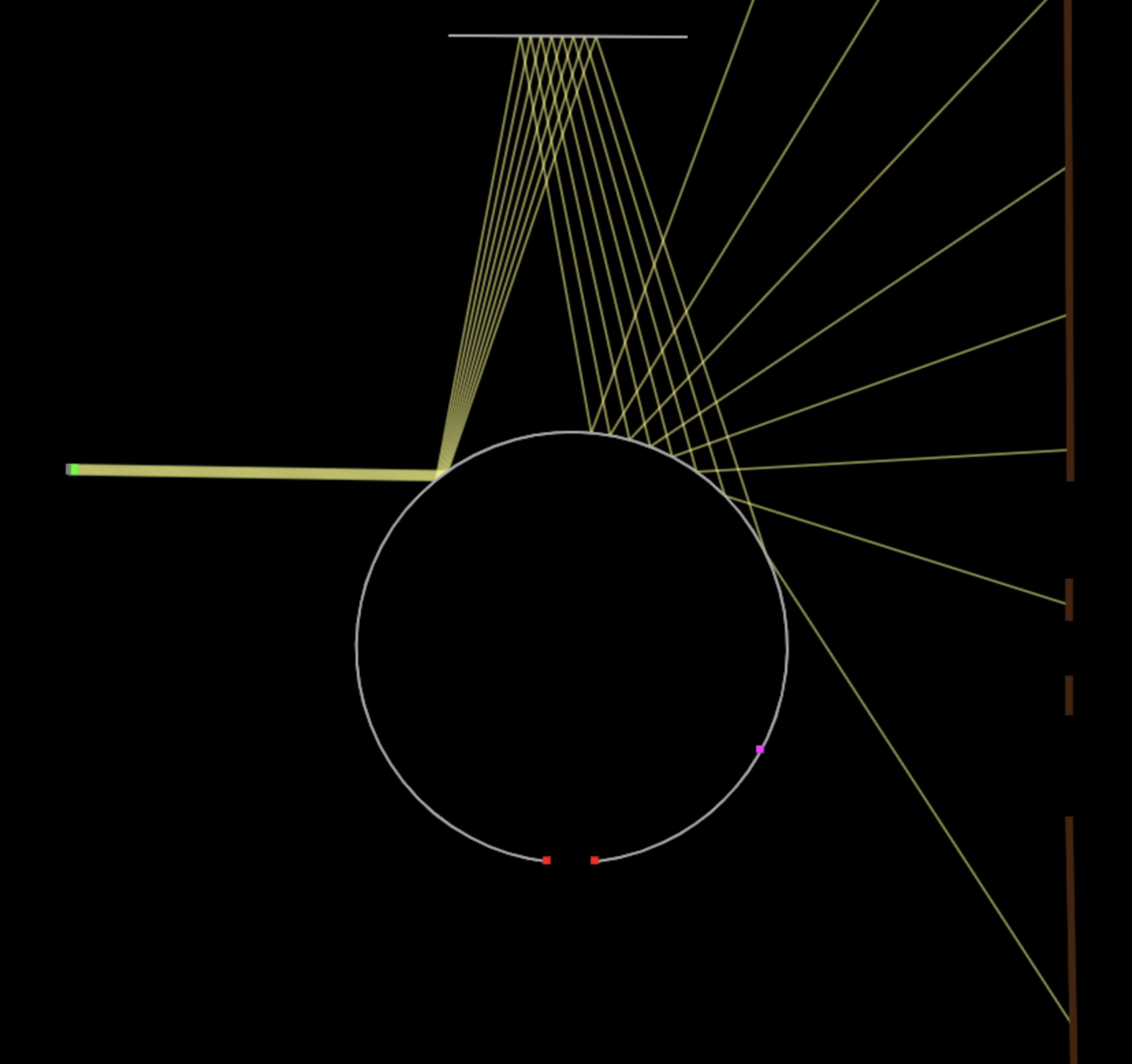

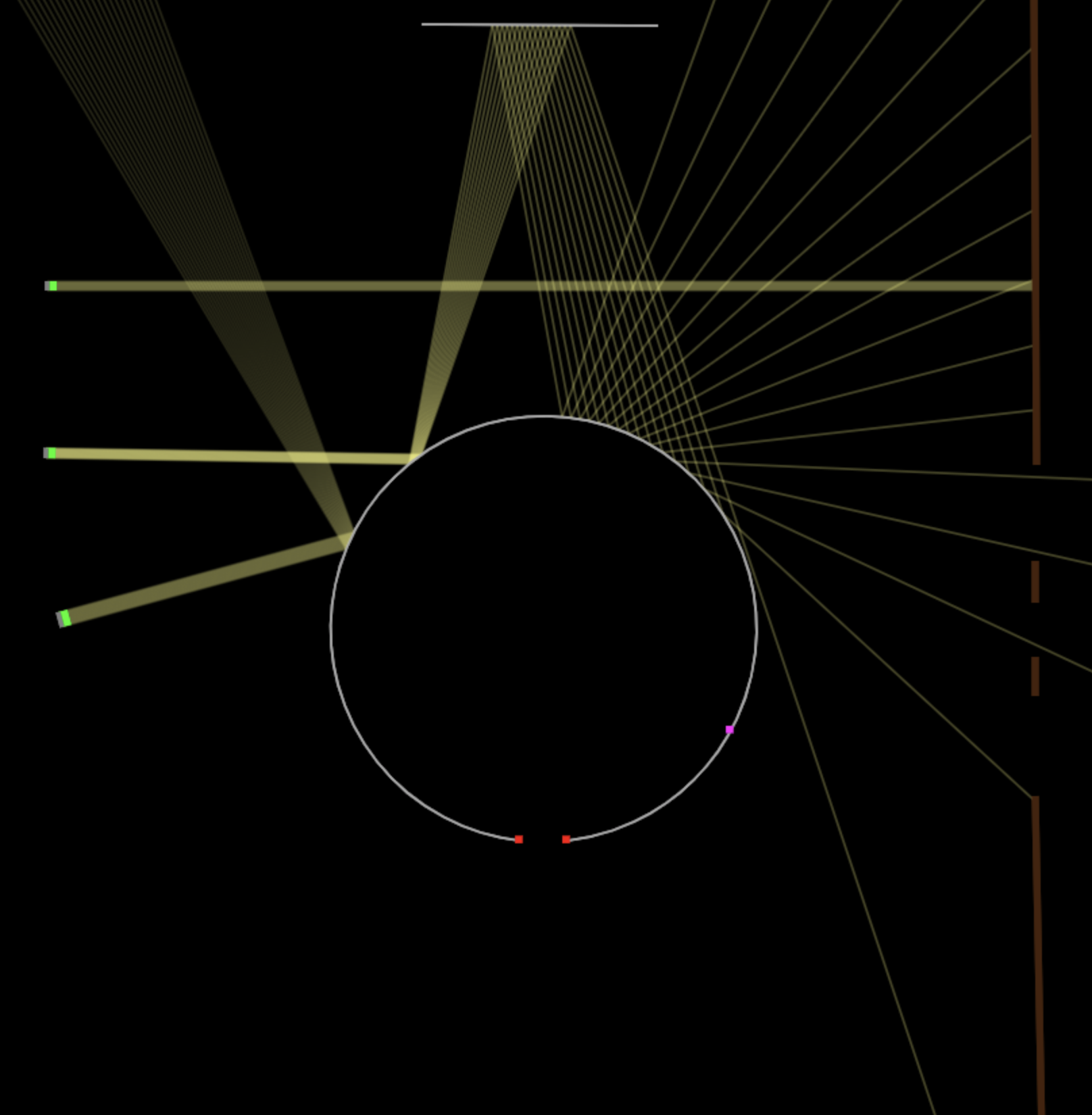

Let’s extend the analogy a bit and modify the above picture to have a “goal” in mind for the

startup. Here, the goal is to pass between the brown barriers on the right side of the image below.

If the line gets through, it means the startup has achieved commercial success and delivered

a solid return to investors. The image below shows 8 startups/lines, and none of them successfully

pass through the barrier. This is generally reflective of the reality of startups – most are not

successful.

One way to maximize the odds of a line getting through is to simply increase the number of lines.

Below, I doubled the number of lines from 8 to 16, and 3 of those end up getting through.

This is equivalent to a fund placing bets on a higher overall number of companies. It’s basically

saying, “It’s impossible (or at least very difficult) to differentiate between companies at the

seed stage, so we’re going to bet on a bunch of them and then inevitably some will be successful,

making the overall fund successful.” So long as the returns from those 3 winners are large enough

to cover up for the other 13 losers, the fund was a success. It’s a perfectly legitimate strategy

that somewhat imitates the index fund approach seen in public markets.

This picture is still far too simple. It’s really only including companies that are starting in the right direction, e.g., they have capable founders, have a path to product-market fit, and are building the right team. The reality is that many, if not most, startups don’t fit this criteria. So the picture is more like the below.

Here, you see 3 different groups of startups. The top group never had a chance – they were generally pointed in the right direction to start, but they didn’t understand the competitive landscape, how their product/service would fit in the market, and went headfirst into a wall. The bottom group is a little different – they start out headed in the right direction, and they’re clearly aware of the obstacles in their path, but these obstacles are simply too big, or the existing players are simply too smart, for these startups to gain additional momentum and stay on track, so they’re thwarted backwards and never achieve success. Only those startups from group B have a chance at success. You can make any number of permutations of these sort of examples, but the governing principle is this: seed funds need to have the ability to throw out companies in the top and bottom groups and invest in companies that are in the middle group – those companies that at least have a chance of being successful. Seed funds that invest in the top and bottom groups have no chance to be successful. Funds that invest in the middle group have some chance. Differentiating between this is both science and art, and undoubtedly some funds are better at this than others.

August 25th 2019

The one and only 20th century

The early part of the 20th century was the greatest period of human innovation, and it will never be topped. Why? Because the 20th century had something that we will never have again…

The oft-repeated idea that we’re now living in an era of unequaled progress and technology breakthroughs is amusing — and flat-out wrong. “We’re making more progress than ever before!” “Innovation is constantly accelerating,” and on and on. To date, the 21st century has woefully underperformed vs. the 20th. Here is an abbreviated list of some of the key innovations from the period 1900-1919:

- 1900: Max Planck plants the seeds of quantum theory by publishing one of the most famous equations in physics: E=hν.

- 1901: First Transatlantic radio communication. For the first time, near-instant communications are possible across continents and oceans.

- 1903: The Wright Brothers fly the first heavier-than-air aircraft. One year later, they develop this into a pilot-able fixed wing aircraft.

- 1905: Einstein develops a theory of Special Relativity, uniting the concepts of space and time. He publishes perhaps the most famous equation ever: E=mc2

- 1909: Fritz Haber synthesizes ammonia, and Carl Bosch industrializes Haber’s process in a BASF lab. So was created the Haber-Bosch process for producing ammonia for fertilizer. This invention, which is the most important in the history of chemistry, single-handedly enabled the global explosion in population that completely transformed the world.

- 1911: Ernest Rutherford theorizes the existence of atomic nuclei. We now know there’s a really small nucleus with electrons orbiting around it.

- 1913: Henry Ford invents the moving assembly line, transforming manufacturing and enabling production of mass goods in a way that was never before possible.

- 1915: Einstein publishes a theory of General Relativity, perhaps the single most creative idea that has ever occurred in the sciences.

- 1917: Rutherford creates the first artificial nuclear reaction.

And things don’t slow down in the years that follow: the 1920s include inventions like refrigeration and penicillin. The 30s have jet aircrafts. The 40s have the transistor. You get the idea.

It’s actually mind-boggling how much happened in the beginning of the 20th century. But why was so much change and progress concentrated in such a small time period?

Globalization.

All of the sudden, travel became much easier. Communications became near instant. Ideas and goods were flowing faster than ever before. What resulted was one of Nassim Taleb’s Black Swan events: an explosion in creativity and innovation driven by an unprecedent sharing of ideas. The world shrunk dramatically in a one-off event that played out over the first few decades of the 20th century.

This isn’t something to lament: we’re all massive beneficiaries of living in this post-20th century world. But — and I’m far from the first person to point this out — it does have implications for how we should frame our expectations around global economic growth. One example of this: economist Robert Gordon lays out his perspective on this exact topic (plus more) in a TED talk from 2013.

There will inevitably be transformative breakthroughs this century, powered by massive compute power and advanced AI that is opening up whole new fields of study. Biology and medicine stand out as fields most likely to experience a golden age in our lifetimes, just as physics did last century. Understanding the human brain and consciousness, cracking the aging puzzle, and solving the energy problem are all outstanding ‘grand challenges’ that will one day be cracked, and the world will never be the same. There are a whole host of new, innovative companies pushing on these fronts and many others that give reason for optimism and keep me excited about investing in the next wave of innovation.

That said, we shouldn’t lose perspective on how truly unique the first part of the 20th century was.

August 22nd 2019

A few thoughts on podcasts

I love podcasts. Like many people, the time I spend listening to podcasts has been increasing significantly over the last few years. They're basically on-demand talk radio: the principal concept isn't particularly new. What is new is the environment in which podcasts exist today.

I think a big part of the appeal is driven by the 'human element': podcasts feel like conversations (because they are), but they feel like a conversation that you're a part of. You feel a connection to the host and guests that is unique among most mediums. Podcasts sit in a happy space between books and blog posts (which are heavy on substance and polished), and Twitter/Instagram/social media (light on substance, mostly unpolished). A good podcast stimulates intellectually like a good book, but with a touch of 'realness' and in-the-moment spontaneity that is impossible in writing.

Podcasts, compared to social media, are incredibly slow: the publishing schedule is more akin to a newspaper than it is to Twitter or Instagram. But this is key: it raises podcasts' overall quality because there has to be enough depth in the content to remain relevant for days or weeks at minimum. The best podcasts will be relevant for decades, much like a good book.

I've listened to hundreds of podcasts at this point, and I'm trying to make a habit of writing down the really interesting things that I hear. Every now and then, really great nuggets come across, and I've likely already forgotten almost all of them. Part of the goal of this space is to help drive that and create some accontability for myself.

Great podcasts I've listened to over the past few weeks:

- Naval Ravikant on Joe Rogan. This is one of the better podcast episodes I've ever listened to. Naval is incredibly well-read and eloquent in communicating his principles of life. One moment that really stuck out to me was when Naval and Joe discuss a Confucius quote: "Every man has two lives, and the second starts when he realizes he has just one." Here's another site looking at some of the wisdom Naval dishes out.

- Peter Thiel on Eric Weinstein: One of the most fascinating people alive continues to intrigue in this episode of Eric Weinstein's new podcast 'The Portal.' Peter Thiel is the ultimate contrarian and always comes to the table with a unique (and often unpopular) perspective. He is a modern philosopher in the truest sense of the word. His fundamental guiding principle ("reduce violence whenever possible") comes through in fascinating ways regarding his views on politics and the roles of governments in people's lives.

- Charles Koch on Tim Ferriss: I left this episode realizing I previously had very little idea what Charles Koch stood for. He comes across more Warren Buffett than 'supervillain.' His guiding principle revolves around setting up systems (whether corporate or government) that enable people to fully realize their potential.

- Chris Bloomstran on Patrick O'Shaughnessy: In this Invest Like the Best episode, Chris shares his fascinating perspective on a variety of topics, the most interesting of which to me was his perspective on Berkshire Hathaway and how Warren and Charlie have been able to evolve the business over the decades.

August 21st 2019

Day One

This is the first day that the site has been available publicly. I developed this site to teach myself the basics of HTML and to understand the mechanics behind getting a website up and running. It's a 'free time' project that I've enjoyed making up to this point and will hopefully enjoy moving forward. A few thoughts/comments on the process:

- I will be continually messing with various features of the website: I will almost certainly break many parts of it, so apologies in advance.

- The site is hosted on AWS. Their documentation was excellent and I didn't have too many issues getting a dummy version of the site up and running.

- While I have some programming experience, I'd never worked with HTML: it's surprisingly easy for the most part. Based on the few days I've spent with HTML so far, documentation does not appear to be as strong or as clear as with other languages like Python and Java (which I'm reasonably familiar with). That said, there are huge amounts of sample code online. I also didn't take the time to learn fundamentals: I jumped right in using sample code and just tried to get a working version of this site up and running as soon as possible.

- Bootstrap is awesome. It allows you to put in fairly sophisticated website elements without too much hassle. Some of the finer points around formatting took me a while to get a grasp on, but overall an A+ for how easy it was to integrate elements from Bootstrap.

Hopefully I'll be able to continue to add content to the site, improve its look and feel, and begin applying more advanced concepts from HTML/CSS.

Privacy Policy and Other Terms and Conditions

Copyright 2019 Brian Huskinson